FOREWARD

I first put this booklet together as the basis of a talk I gave at Kirkland Village Retirement Center in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where my dad, Howard Hill, spent his last ten years having a great time.

That was back in 1999. Recently I was asked if I'd make it available again, which I'm happy to do. To accommodate the great advances in recording/writing/printing technologies (back then it was VHS and cassette tapes, and nobody had ever heard of a blog), I've become less specific about the details and cost of them in the "How to Do It" section.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Why Should You Write Your Memoirs?

PART 1 -GETTING STARTED

Who Might Want to Read Your Memoirs and Why?

Finding Your Voice

How To Be Yourself While Maintaining Your Privacy

The Metaphoric Voice

The Selective Voice in Action

Sticking to What You Know

Truth and Imagination

How Much Should I Tell?

PART 2 - HOW TO DO IT

WRITING IT DOWN

The Pad-and-File-folder method

The Essay Method

Some Writing Hints

Scribbling Away

Keeping At It

Outlining

RECORDING

Recording Equipment

Recording With an Interviewer

Transcriptions

Farming it Out

Once Your Recordings Are Transcribed

EDITING YOUR LIFE

WRITING WITH OTHERS

Group Interviews/Discussions

Writing with a Friend

Group Writing

INCORPORATING OTHER MATERIALS

Visuals and Sidebars

WRITING MY OWN MEMOIRS, ONE THURSDAY AT A TIME

SAMPLE QUESTIONS FOR PONDERING AND INTERVIEWS

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

INTRODUCTION

I was once introduced to a retired Welsh Presbyterian minister named Elam Davies, a gentleman whose distinguished career had included British Intelligence work in WWII and more than five decades as pastor to assorted congregations scattered across two hemispheres.

Though a very learned man, Elam Davies had just made a very common error—he heard the word “memoirs,” and confused it with the term “autobiography.” As a result, he was under the impression that in order to write his memoirs, he had to start from the beginning and set down every last detail of his long and complex life in precise chronological order—a daunting task for even the most dedicated writer or storyteller.

Fortunately for Dr. Davies, and for all of us, that’s not precisely the case, for although an autobiography can be a memoir, a memoir doesn’t have to be an autobiography.

Confused? Here’s the main difference between the two:

Autobiographers are generally expected to start from the moment of their birth (or even before) and churn out a fairly complete and detailed chronological history of themselves, one which reads from beginning to end like the notes on a page of sheet music.

A memoir, on the other hand, is more like humming a tune from memory—it can be as brief, as episodic, and as sweetly subject to personal eccentricity as its author pleases.

This leads to another specific difference between the two approaches: autobiographies often tend to deal primarily with facts; memoirs, on the other hand, deal mostly with memory and atmosphere.

“Writing a memoir” explains editor William Zinsser, in his introduction to Inventing the Truth, the Art and Craft of Memoir (Houghton Mifflin Co., 1987), “is a process of sorting out your memories and emotions and arriving at a version of your past you feel is true.” He quotes author Gore Vidal, who in a 1995 New Yorker piece called “How I Survived the Fifties,” made the following observation:

A memoir is how one remembers one’s own life, while an autobiography is history, requiring research, dates, facts double-checked. I’ve taken the memoir route, on the grounds that even an idling memory is apt to get right what matters most.

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Why Should You Write Your Memoirs?

If you’re as modest as the rest of us, you might think: “Who in the world would want to read my memoirs?” You’d be surprised; every one of us has a story worth telling. You may think of your life as uninteresting to others, but, as with life itself, it’s all a matter of perspective.

Humans have a built-in fascination with bygone days, and to your great-grandchildren (or to an anthropologist 200 years in the future), even the most mundane details of your personal history can be a source of immense interest. By setting down your own memories, you can actually become a voice from the past, bringing it alive for future generations. Much of what we know of life in previous centuries, for instance, comes not from ponderous historical works, but from the letters, diaries, household books and memoirs of ordinary people.

And all you have to do is get it down on paper. The purpose of this booklet is to give you some practical hints and methods for doing just that, especially if you’re not by nature a writer or storyteller.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

GETTING STARTED

If you've gotten this far, perhaps you’ve already decided to write your memoirs, or are at least curious enough about the process to continue reading. If so, the first question you need to ask yourself about memoir writing, even before “How?” is “What’s my motivation?”

Let me hasten to assure you that there are no wrong answers to this question. It’s just that figuring out why you want to pass on your memories makes it easier to identify the readership for whose benefit you’re writing them. This in turn may help you figure out which portions of your life story are the most appropriate to relate.

Here are some reasons that people have written memoirs in the past. Do any of them ring a bell for you?

1. To leave a historical record of themselves for their descendants. (Examples: The Education of Henry Adams by Henry Adams; or Having Our Say—The Delaney Sisters’ First Hundred Years by Elizabeth and Sarah Delaney)

2. To give a feeling for the place(s) and time(s) in which they lived. (Russell Baker’s Growing Up, Annie Dillard’s An American Childhood)

3. To give their impression of famous people they’ve known or well-known historical events or eras they’ve been a part of. (Ron Kovic’s Vietnam-era book Born on the Fourth of July; Life with Rose Kennedy, by Barbara Gibson)

4. To celebrate loved ones and/or family members. (I Remember Mama, by Kathryn Forbes; My Sergei, by Ekaterina Gordeeva)

5. To celebrate a particular country or a place. (Out of Africa, by Isak Dinisen; Alfred Kazin’s A Walker in the City)

6. To set an example or expound a philosophy based on lifestyle choice. (Thomas Merton’s The Seven Story Mountain; Alan Watts’ In My Own Way.)

7. To celebrate a profession, an avocation, or a specific kind of experience. Mark Twain’s My Life on the Mississippi; Antoine de St. Exupery’s Wind, Sand and Stars),

8. To tell the story of the overcoming of obstacles and/or rise to success, fame or power. (Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself; My Life in Court, by Louis Nizer)

9. As a vehicle for fictional literary expression of events in one’s life. (The Joy Luck Club, by Amy Tan; Little Women, by Louisa May Alcott)

10. To reveal secrets, or deeply personal thoughts. (Hitler—Memoirs of a Confidant, by Otto Wagener with Henry Ashby Turner; Royal Secrets—The View From Downstairs, by Stephen P. Barry)

11. To tell their side of the story/set the record straight. (Child Star, by Shirley Temple Black; Keeping Faith: The Memoirs of a President, by Jimmy Carter)

14. To get even. (An Age of Mediocrity: Memoirs and Diaries of C.L. Sulzberger; My Turn: The Memoirs of Nancy Reagan)

These are the most common motivations behind memoir writing. Maybe your reason for wanting to do it is something else entirely, but it’s extremely helpful to get that reason clear to yourself before you begin.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Who Might Want to Read Your Memoirs and Why?

Once you’ve figured out the most likely reason for writing your memoirs, the next question to ask yourself is: for whom am I writing this? Here’s another list, this one of possible interested readers and reasons for addressing a memoir to them:

1. Yourself - As a writing exercise; as therapy or as catharsis (getting it off your chest); to exorcise painful memories; to help yourself relive or remember interesting or important events in your life.

2. Your spouse, children, extended family, or descendants—To share your memories; to give them information you’ve never been able to tell them in person; to give them a better idea of who you are; to contribute to their knowledge of family history; to tell your side of a family dispute.

3. Posterity - To contribute to the general or historical knowledge of an era; to be remembered after you’re gone; to keep your personal or family history alive.

4. The General Public - Because you think you can amuse, entertain and enlighten them; to give them your impression of events of your day; to cast new light on well-known people, places or historical events if you have an association with them.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Finding Your Voice

If you’ve ever read and enjoyed the memoirs of others, you know that it’s not really enough to just write down a bunch of facts; every memoir needs a personality and a “voice” behind it, preferably the author’s. Many people, however, have the mistaken impression that their real voice somehow isn’t good enough for posterity, and they want to fancy it up somehow.

One temptation to be avoided when setting down a memoir is actually trying to be “literary,” or to write in an ”elevated” style. It’s also best not to affect a “folksy” style, unless you were brought up in a region where speech is distinguished by dialect and colorful imagery, and this style comes to you naturally and is your usual means of communication.

Here’s a good rule of thumb: the more artificiality and distance you put between yourself and the reader, the less your writing will appeal to others. Although you naturally want to be readable and lively, an attempt to impress your reader by adding frills, or hiding behind a “dress-up” personality, often tends to distract from the real purpose of a memoir, i. e., to communicate the actual flavor of your life along with your words and thoughts about it. Ultimately, the verbal rhythm in which you yourself normally think, talk, and write is the best cadence for setting down your memories.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

How To Be Yourself While Maintaining Your Privacy

This is not to say that distancing tactics cannot be used. One such tactic is simply to choose only those topics you feel comfortable relating, and write about them in a more or less reportorial style. Most memoirists and fans of memoirs will tell you, however, that it’s often those things which are most uncomfortable to write that have the power to move the reader the most.

An example of this was related in a 1986 lecture by columnist Russell Baker. In the process of writing his powerful memoir, Growing Up, Baker first submitted to his editor an accurately reported recollection of his childhood, only to realize, on re-reading it, that it was a failure as a memoir:

“...the problem was,” Baker remembers, “that I had been dishonest about my mother. What I had written, though it was accurate to the extent that the reporting was there, was dishonest because of what I had left out. I had been unwilling to write honestly. And that dishonesty left a great hollow in the center of the original book.”

Rewriting his memoir in terms of the life-defining relationship between him and his mother, Baker lifted it out of the realm of the ordinary and into the remarkable.

Not all of us, however, want to set down our innermost thoughts and intimate struggles, and not all of us should. If you tend to be a humorous or ironic observer of your life and times, then that may well be your most effective voice. If you’re an avid correspondent, a racy raconteur or a simple storyteller, these are all valid voices for a memoirist.

As mentioned, the ideal voice is, of course, the one that is closest to your own. All of us have read the memoirs of simple people who, by speaking clearly and truthfully, using no devices or disguises, have the power to move us profoundly. One the most powerful of these, for example, was Anne Frank, who in a simple schoolgirl diary brought home to untold numbers of readers the everyday horrors of war.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@

The Metaphoric Voice

One way to enliven a memoir without baring your soul is to couch it in the form of an extended metaphor. My friend Chester Aaron is the author of a memoir entitled Garlic is Life (Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, CA, 1996). Besides being a charming fellow, a robust senior citizen and a delightful writer, Chester is also a specialty gardener who grows dozens of unusual varieties of garlic for use by top chefs in exclusive restaurants all over the country.

Chester’s memoir, like his current life, is infused with the aroma and presence of garlic: memories of his father planting it and his Russian-immigrant family cooking with it, his own introduction to growing it, its gradual permeation of his life and interests, the obstacles and challenges which beset his rise to prominence as a specialty grower, and the mentors, friends, relatives, oddballs, cats and garden pests encountered on the way to becoming an internationally recognized garlic maven.

Throughout the book, these anecdotes from Chester’s life-in-garlic are deliciously mingled with the plant’s history and taxonomy, garlic-based recipes, jokes, folktales, horticultural secrets, even the results of a garlic taste-off. And beguilingly interlaced with his love for Allium sativum are delicate hints of a personal love story of his own.

One of the most interesting things for me about Garlic is Life is that it is a fine example of a memoir that is both very personal and selectively so. I happen to know that besides being a garlic aficionado, Chester was a soldier in WWII, and was present at the liberation of Dachau; that he is also a celebrated author of books for young people; that he holds certain political views. None of these particulars, however, appear in Garlic is Life. By writing a selective and metaphoric memoir centered on something he loves, Chester has found a way to write with passion while maintaining his own comfort level of privacy.

The Selective Voice in Action

Another memoir that transcends mere reporting, while still maintaining privacy and objectivity, was written by my friend Margery “Maudie” Sell. This small book, entitled Wherever You Are, had its origin in a local writing class and was printed in a small edition intended primarily for family and friends.

On the surface it’s a fascinating account of the WWII years in which Maudie, now in her seventies, served as an American Red Cross “Donut Dolly,” driving around the battlefields of Europe in a truck with two other women, a donut-making machine, a Victrola and a stack of jitterbug records.

Her accounts of doing her part for the morale of soldiers on the front by making donuts for them, dancing with them to the latest tunes and talking to them of home (often with the sounds of battle audible in the background) are fascinating enough. Still more absorbing is the hidden agenda implied in the title, a reference to the fact that she did this emotionally difficult and often physically dangerous job as a means of staying on the same continent as her husband Arthur, then a U.S. Army tank commander.

There are no great romantic declarations in Sell’s text, no amorous details involved in the descriptions of her brief meetings with Arthur—often achieved at the cost of great hardship—in embattled spots all over the European theater of war. But quietly laced through this humorous and remarkable tale of bravery and adventure is an unforgettable love story.

Sell’s book, treasured by those lucky enough to receive a copy, is a real-world example of maintaining dignity and distance in a memoir without sacrificing passion. And Maudie and Arthur’s children and grandchildren, by the way, are thrilled to have access to this deeply personal story by a very private individual.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Sticking to What You Know

Critic Alfred Kazin, author of a marvelous memoir called A Walker in the City, which sets forth vivid memories of his boyhood in the Brownsville district of Brooklyn, originally began the book as an artistic attempt to describe post-WWII New York City; eventually, however, he was forced to confront his authentic voice and metaphor:

“What I went through for an absurdly long time trying to hammer the [book] together does not deserve extended description here. Finally, I realized [that] the only thing emotionally authentic in my vast manuscript was those carelessly scribbled pages about growing up in Brownsville. On those, once I realized just how sensory the material really was and how vivid the prose would have to be, I could build my memoir.”

Kazin, like Maudie Sell, opted for a small section of a large topic. Rather than write about an entire city or an entire war, both of these memoirists selected stories that they actually lived, and the details of those stories that were most vivid in their memories. This is a hallmark of the most successful memoirs—people writing about what they really know and love instead of hiding behind a window-dressing of historical facts, political opinions or impersonal details.

Another aspect of a good memoir is the sense that it could have been written by no one else. My friend Arnold Levine was once a "radio pirate," transmitting from dozens of secret London locations in defiance of the stultifying regulations imposed by the British Government and the BBC. From the website of the resulting memoir, Banned By the BBC!:

"Written by the co-founder of notorious pirate station Radio Concord (1971-77), this personal memoir spans the never-before-told inside story of pirate radio, squatting, punk music, social issues, and revolutionary politics roiling in the demi-monde of 1960s and 1970s London."

Arnold's experience, told in this context, contains the unique I-was-there voice that characterizes any well-written memoir, whether of radio piracy or visits to Grandma's house.

@@@@@@@@@@@@

Truth and Imagination

So where does your imagination come into memoir writing, especially if you plan to stick to the truth? Writer Toni Morrison gives the perfect answer to this question in an essay called The Site of Memory:

“The act of imagination is bound up with memory. You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact, it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was. Writers are like that: remembering where we were, what valley we ran through, what the banks were like, the light that was there and the route back to our original place. It is emotional memory—what the nerves and the skin remember as well as how it appeared. And a rush of imagination is our flooding.”

There’s not much to add to that, except to say that if you embroider on the facts too much, someone who was there is bound to pop up and face you with it. At that point, you can either apologize and re-write your account in a way that integrates the memories of both of you, or tell them to write their own damn memoir.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

How Much Should I Tell?

How much should you tell in your memoirs? As much as feels comfortable to you, given your motive for writing them in the first place. Again, one of the first steps you’ll have to take in the memoir process is defining that motive. Do you want to amuse and/or entertain? Inform? Justify yourself? Get revenge? Tell things your way? Celebrate your life with another person? Reveal a you nobody knows? The clearer you are on this, the clearer your writing is likely to be.

Consider also your intended audience and the impression you want to leave them with. If you’re writing for the general public, you may want to (1) carefully avoid or (2) gleefully include embarrassing information about other people who appear as characters in your life.

If you’re writing for your children, you may or may not wish to stir up old family grudges or include intimate details of your sex life with their other parent. (See also Annie Dillard’s comments under “Editing Your Life,” below.)

A good rule of thumb is to put yourself in the place of the memoir’s intended audience and imagine how you’d feel reading it. If tittilation or shock is in fact your goal, go ahead and tell all. If it’s important to you to maintain a public image, you may not want to reveal anything that contradicts that image.

(A note of warning on this approach, however; it will probably not fool those readers who know you, and comes under the heading of a “false voice,” as discussed above.) Ultimately, it’s best to keep your audience in mind and write or talk about those things that suit both your motivation and your comfort level.

PART 2 - HOW TO DO IT

(Note: when I originally compiled this booklet in 1999, digital recording was in its infancy, and audio- and videotape were the usual vehicles for preserving memories. Since then, so many new recording and voice recognition technologies have emerged that I’m not going to try to keep up with them. Most of the hints below can be applied to any recording technique.)

There are basically two methods for getting your memoirs out of your mind and onto paper: 1) writing them down, or 2) recording them for transcription. Voice-recognition software, for dictating directly onto a computer document, is a third option, although it also can result in comical errors that need to be edited.

Video is actually a fourth option if you aren’t camera-shy, don’t like to write, and want to leave a visual memoir as well as a verbal one. Many of the suggestions below that apply to audio can be used with video as well.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Writing It Down:

With the exception of professional writers, avid correspondents, or faithful journal-keepers, this is the part that stalls most people in their tracks. In this day of cellphones, texts, and e-mail, many of us are no longer used to reflecting on our words, organizing our thoughts, and setting them down at length on paper. If you’re one of those lucky people who think best with a pen or computer mouse in your hand, or simply find the idea of writing more interesting than voice-recording, there are a number of ways to harness your enthusiasm for the written word.

(Incidentally, one of the most valuable tips on memoir-writing I ever learned was to write as if recounting your memories to a dear friend. Another is to read your work out loud to determine its rhythm on the page.)

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

The Pad-and-File-folder method

One useful method of gathering thoughts is to carry a small notepad.; when you find yourself, in the natural course of events, remembering or reflecting on a past experience or story, jot down a brief note about it.

You don’t have to write your finest prose at this stage, or even set down complete sentences, just scribble a few choice words that will jog your memory the next time you see them. When a page is full of notes on one side (using both sides can get confusing), tear it out and put it in a file folder marked “Memoirs,” or whatever name you prefer. (Some version of this technique may also work with a small digital voice recorder or cellphone, but this adds the necessity of transcribing to the process.)

One added benefit to the hand-writing method is that, should you never do more than this before passing on, there will at least be a clearly marked folder full of tantalizing scribbles to intrigue those who come after you. (Computer users may want to transfer their scribbled or recorded notes verbatim to a “Memoirs” computer file on a regular basis.)

When you feel as if you’ve accumulated enough notes, you may be motivated to sort your jottings into a number of other files, again, easiest with paper for many people. One way to organize them is timewise, e.g., “Birth to Age Five.” or “1930-1940.” Another is by category—“Family,” “School,” “Work,” etc. These can be broken down into sub-files if you feel it necessary, e.g. “Grandparents,” “First (Second, Third) Job,” or “Elementary-school Years.”

In the process of creating your files (maybe even with your very first set of jottings), it’s likely that one or more of these scribbles will generate the thought “I could really enjoy writing something about that.” That’s the point at which you should take advantage of that feeling to sit down and begin to put your memories down on paper. (See “Some Writing Hints,” below)

To give you an idea of how this method can work, here are some briefly jotted notes of mine, and the memoir section that eventually resulted from them:

WHAT I WROTE IN MY NOTEBOOK:

“Visitor/check/Pennsylvania regional names/German settlers/Koose/Foose etc.”

WHAT I EVENTUALLY WROTE:

Recently a customer came into the Northern California store where I was working, made a purchase and paid for it with a check. The address printed on the check was in California, but the name “Riehl” brought a smile to my face. “I bet I can tell you where you or your parents were born,” I said, “Somewhere near Northampton County in Pennsylvania.”

The man was amazed. “How did you know that?,” he asked.

It turned out he’d grown up within 12 miles of where I’d been raised, gone to a rival high school, and knew a number of my friends and classmates.

How did I know where he came from? By his name, which is one of those you barely ever encounter anywhere else. I, like Mr. Riehl, grew up in a small region where people were called extraordinary things. The Pennsylvania Dutch who populated this area just north of Amish Country were not members of picturesque German religious groups like the Amish, Mennonites or Moravians. They were simply small farmers, craftsmen or shopkeepers who had been caught up, with or without their families, in various waves of immigration triggered by religious persecution or poor economic conditions back in Germany.

Mammy Morgan’s Hill, the area to which my parents had moved in the 1940s, had originally been settled by poor, hard-working and mainly illiterate German peasants. Established years before the American Revolution on what was to become Morgan’s Hill, these hardy immigrants generally came from the same small region of Germany and spoke an obscure version of Plattdeutsch (low German) that became more cryptic with each generation. The names of these people tended to be either unusual dialect approximations of German or vivid descriptive terms reminiscent of Native American or Early Anglo-Saxon naming traditions.

And so it was that, along with trade-related names like Kichlein or Kachlein (Little Cook), Ruschman (Cutter or Seller of Rushes), Sherrer (Sheep-shearer), and Brotzman (Baker), I grew up with playmates whose surnames were even more picturesque and evocative: Dornblaser (Thornblister), Unangst (Fearless or Unafraid), Schwarzbach, Trittenbach and Hagenbach (Dark Brook, Running Brook, Acorn Brook), Bonstein (Polishing Stone), Hirschtritt (Deer Step) Pickel, (Pimple), Gutekunstler (Good Artist) and Trumbauer (Bad Farmer).

And then there were those classmates whose last names were odd monosyllables that bore little or no correspondence to their German originals, having devolved to more basic versions—Kutz and Butz and Dutt, Schruntz and Schrindt and Schramm and Schnorr, Fluck and Frindt, Koose and Foose, Diehl and Riehl. Even today, hearing one of them evokes vivid childhood memories of rural Pennsylvania, one-room schoolhouses, and sharing desks and playgrounds with kids with magical names.

@@@@@@@@@@@@

The Essay Method

The above example of memoir writing is in essay form. Most people remember being asked to write school essays at one time or another in their lives, and thus most are at least familiar with the form, defined in the American Heritage Dictionary as “a short literary composition on a certain subject, usually presenting the views of the author.” The essay form is especially handy for the aspiring memoirist because it can stand alone, has a distinct beginning and end, and can be pretty much any length the author desires.

Thus, if you find the idea of describing your life from beginning to end a daunting one, you may be much more comfortable thinking in terms of a series of short essays based on events, people and places you have known.

My father, for instance, produced a remarkable book of informal memoirs (which he titled Out of My Mind: Stories for the Front Porch) by setting down one- or two-page observations of his many interesting life experiences and memories. He wrote these mini-essays one by one over a numberof months, taking advantage of those times when he found himself wide awake in the middle of the night to get up and do something constructive.

By the time his first notebook was filled, he had produced a fascinating study of his childhood and early adulthood, his family in Arkansas, and his many memorable interactions with interesting people over the years. In doing so he created, in just a few short hours a night, a memoir that is cherished by his children and other family members.

This short-essay approach, besides dividing the memoir-writing process into manageable pieces, gives you the option of presenting only the portions of your life and thoughts which you feel like sharing, and doing so without leaving any big gaps in a chronological narrative.

An essay can cover small anecdotal experiences (“The Time Aunt Mayme took off her Corset in Church”) or more comprehensive ones (“My Years with the Circus”). It can be highly personal (“Why I became a Buddhist”) or generally philosophical (“If I Had It All to Do Over Again”). It can contain useful information (“How Grandad Charmed Warts Away”) or specifics that you want to pass along (“My Up-to-Now-Secret Recipe for Blackberry Fritters.”)

Recipes, by the way, like photographs (see “Incorporating other Material”), have served as inspiration and pacing devices for many a successful memoir. When you write about a recipe, you can include the story of how it came into your hands, of people who liked (or disliked) it, of memorable occasions when you served it and what happened, etc.

Food in general is a great source of memories. My uncle Dus can wax rhapsodic over his Aunt Tonkie’s recipe for fried banana rolls, while Aunt Dortha naughtily admits that the reason her uncle gave for never eating boiled okra (one of the world’s slimiest foods) was that “he was afraid he’d find it in the chair when he got up.” Remembering favorite foods or extraordinary meals (and the people and events surrounding them) is a time-honored literary device to get your memoirs cooking.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Some Writing Hints

A memoir is most likely to be read if its writer is enjoying, or is at least stimulated by, the writing process. If writing certain details bores you, they’ll probably bore the reader, too. Here’s a good way to keep yourself interested: when you sit down to write, mentally review all the possibilities and stories that you’ve created files for and go straight to the one that tugs at you the hardest. You can even create an entirely new one, if that’s what it takes to get your juices flowing.

Feel free to switch from one chapter or essay to another at any time. For instance, in working on the early stages of this booklet, I quickly created, as the subjects arose in my mind, computer files entitled “Introduction,” “Why Write Your Memoirs?,” “Method,” “Writing Hints,” “Style,” “Incorporating other Material,” etc., flashing between them to add material, and adding new files as new subjects arose.

Then, whenever I had a thought that belonged in one of those categories, I had a place to set it down. Your version of this personalized-file process could include areas such as “School,” “Mom and Dad,” “Best Friends,” “Special Events,” “Pets,” “Train Rides,” “AA Meetings”—you get the idea.

If you get bogged down on one area or period of your life, try switching to another that you consider more interesting. It may even give you some insight into why you’re bogged down on the first one. If there’s a subject you thought at first you might like to cover but now find you just can’t get into it, you may simply not want to write about it for posterity. (But keep that file; you may change your mind.)

A cautionary note here: you may want to set some kind of personal limit on starting too many new stories, especially if you haven’t finished those you’ve already begun. Otherwise you’ll just end up with a bunch of beginnings (so to speak). While writing is generally best done with a sense of eagerness and interest, sometimes you just have to bite the bullet and complete something you’re a little tired of. You (and your descendants) will be glad you did.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Scribbling Away

The most important thing to remember about writing is: get it down! Don’t bother agonizing over style or word choice at first; write stream-of-consciousness or disconnected word-associations if that’s all that comes. You can always rewrite and revise and rearrange later (but you may not even need to).

Remember, this is your project, and any way you want to do it is valid. In a memoir, no subject matter is forbidden, no particular structure or writing style is mandated. The important thing is to get the image, memory or quote down before it gets lost.

My friend Faith Craig Petric is a remarkable woman in her eighties who has long been a prime mover of the lively San Francisco folk-music scene and a powerful singer/storyteller in her own right. Recently, she tells me, she’s taken up a habit recommended in a book on unlocking creativity, The Artist’s Way, by Julia Cameron.

As recommended by Cameron, each morning Faith sits down and writes three pages of anything at all—free-association, opinions, stories, song lyrics, complaints, poetry. Lately, she says, she finds herself writing about the past, not every day, but when the spirit moves her, and that she has made a real start on a collection of memoirs.

She says “When you first start writing—and I think it’s true for a lot of beginning writers—you’re scared to death that if you don’t get that sentence just right in that very minute it’s never going to show up again. And it isn’t. But it doesn’t matter—another one will, and it’ll probably be better.”

My dad reminds me that author Walter Gibson (creator of the unforgettable character known as "The Shadow") used the device of stopping a work period while in the middle of a sentence so that he could at least begin his next writing session by finishing that particular thought, in the hope that it would provide the necessary momentum to

Keeping At It

continue writing at the beginning of the next session.

One of the best ways of staying with your task is to make an appointment with yourself to work on your memoirs at a specific time each day, or on specific days of the week, and keep that appointment. If you frequently allow other things to pre-empt your writing time, then writing your memoirs can just become one more thing you always meant to get around to and never did.

Essayist Annie Dillard offers an astute observation on the attitude which makes people stick to a writing project:

Writing is like rearing children—willpower has very little to do with it. If you have a little baby crying in the middle of the night, and if you depend only on willpower to get you out of bed to feed the baby, that baby will starve. You do it out of love. Willpower is a weak idea; love is strong. You don’t have to scourge yourself with a cat-o’-nine-tails to go to the baby, You go to the baby out of love for that particular baby. That’s the same way you go to your desk [to write].

Dillard makes a good point; writing your memoirs shouldn’t be an unpleasant must-do-should-do chore that takes all your willpower and no love; if it turns into one, you’d probably be better off taking tennis lessons or improving your needlepoint.

If the thought of writing for yourself or for posterity doesn’t give you a pleasant little thrill, the only other reason to do it is out of love for those who will eventually read it. If either or both of these conditions is present, you’ll be able to maintain momentum; even if you stop for a period of time, you’ll eventually be impelled to start again, taking up where you left off and building on your previous experience.

This is not to say that it won’t be difficult sometimes; every project has its rough spots. But if you feel as if you’d rather be at the dentist when you’re trying to write, there’s no reason to torture yourself; stop, already.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Outlining

If you’re determined to carry this project through but can’t get the words from your mind to the page, another useful tool for getting things down on paper (especially if you tend to be more organized and less stream-of-consciousness) is creating an outline of the “story” you’re planning to tell in a memoir section or essay.

One good way to outline your story is to pretend you’re telling it out loud to a friend, line by line. “This happened, and then I said and then this happened and then he said, and he was wearing etc.” Pause at short intervals and write down or note briefly the essence of what you’ve just said.

This is also a good way to develop a sense of whether a memory can stand on its own as a separate essay or needs to be incorporated into another. If you’re something of a raconteur, you may find you already possess a collection of well-polished stories all ready to be set down.

Telling a memory aloud also can help sharpen your perception of how you actually speak. If you find you enjoy doing this more than writing things down, you may want to try composing your memoirs as recordings.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

RECORDING

Dictating one’s memoirs is a time-honored way to circumvent the difficulties of putting pen to paper (or fingers to computer keys). Many a 19th-century memoir was created while its perpetrator reclined cozily on a sofa or chaise longue, free-associating to a faithful secretary, companion or long-suffering spouse.

Today, few of us have the services of an amanuensis to take down our smallest syllable, but many of us do have access to something that will, under the proper conditions, perform with even greater accuracy and perhaps less friction—the digital recorder.

What this relatively inexpensive device lacks in human interaction, it makes up for in fidelity and stamina; give it enough battery-power and it will hold out as long as you do, without ever yawning from boredom, complaining of writer’s cramp, or giving you the fishy eye when you embroider the facts a little.

Another advantage of recording your memoirs is that many people simply find it easier to talk than to write, and recording allows the memoirist to take advantage of his/her natural voice patterns and word use instead of having to worry about composing a written piece.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Recording Equipment

The equipment you use can be quite small and unsophisticated, provided that it will reproduce your words clearly and faithfully. Some people like to use a very small digital recorder, often voice-activated, which can be kept in a pocket or purse and taken out when inspiration strikes or opportunity knocks.

These allow the memoirist to record in odd moments such as waiting for a bus or on hold for a telephone call, and provide those Type A personalities with the chance to use otherwise “wasted” time creatively. You will, of course, have to choose appropriate times and circumstances to do this if you don’t want to be the recipient of a lot of funny looks.

You’ll need to find a way of getting comfortable around these devices while still allowing them to pick up your voice clearly. Most recorders have a jack (outlet) for a hand-held microphone.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Recording With an Interviewer

Some people, when faced on their own with a recorder, suffer a kind of stage fright; they find themselves “drying up” and unable to produce a single coherent thought. Often this problem can be worked through by writing down a list of topics to cover or questions to answer, then pretending someone has just asked you these questions. If your experience with imaginary playmates or role-playing is limited, however, you may want to import a real live interviewer.

Some older memoirists will find that a family member (a child, grandchild, niece, nephew or in-law) will be delighted to help them out, and will even come prepared with questions of their own. If this is the case, you’re lucky, since you can be sure that what you’re recalling is what people do indeed want to hear.

If you’ve lived in a community for a long time; known famous or remarkable people; done an unusual and interesting job; or are an authority on a particular subject, a local historian or journalist may be eager to hear you talk about your life. A contemporary can also make a good interviewer, especially if you provide lunch along with an appropriate list of questions. (See also “Working With Others,” below.)

In all these cases, encourage your interviewer to ask any questions that arise naturally for him or her, and be prepared to deviate from your prepared list of topics when spontaneous questions emerge as a result of genuine interest. (You may be surprised at which parts of your life your listeners find the most fascinating.)

The most important part of a recording session is the one where you forget the recorder is running and just start having fun telling stories. (Just make sure the recorder is running.)

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Transcriptions

Once you’ve got your words safely recorded, you or someone else will need to transcribe them (listen to the recording and write down or [preferably] type into a computer what you’ve said); you can also opt to have them transcribed professionally. Many people prefer to do the transcribing themselves, finding that it gives them an opportunity to edit and shape their words as they put them on paper, while also eliminating false starts, injudicious remarks, repetition and extraneous comments. (I tend to write my memoir essays out by hand on lined paper, then edit and elaborate as I put them into a computer writing program.)

The task of transcribing can be made easier by the use of a transcribing machine, which has “forward,” “stop,” “play” and “rewind” functions operated by a foot pedal, as well as controls for speeding up or slowing down the playback speed. These machines, free the hands, eliminate the need for flailing at buttons, and make it simple to back up, go forward or locate a certain spot on the recording, If you think your memoirs are going to be lengthy and detailed, a transcribing device may be a worthwhile investment.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Farming it Out

Rather than producing your own transcription, you may find it easier (though more expensive) to have the entire recording session transcribed by someone else, and then edit it or pick out the sections you want for rewriting. If you’re lucky, you have a friend, relative or local historian who is willing to take on the task for free, or is willing to do it for an amount you can afford to pay.

There are also professional transcribers, usually available online or through the Yellow Pages (are there still Yellow Pages?] of your phone directory. These professionals may charge by the word, the line, the page, or the hour. Word, line and page size are usually subject to negotiation. Nowadays many transcriptions are done straight to computer, so that changes and deletions can be made onscreen.

Another twist on this dictating business is the advent of voice-recognition computer software, which enables its user to dictate straight to print. Such programs can be a little cranky about recognizing unfamiliar words, and will often need extensive editing.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Once Your Recordings Are Transcribed

Depending on the type of memoir you plan to write, your transcribed recordings, once printed out, can either serve as raw material or finished product. Once you’ve got your words/thoughts down on paper, you may wish to leave them just as they are for posterity, or to give them a more formal shape through editing, choice of sequence, or elaboration. The contents of your transcripts, when you read them through, may also remind you of something you feel is missing, or trigger the urge to share more stories and memories. Listen to that urge.

Here are some things you can do with your transcriptions:

• Organize them by subject or chronologically.

• Edit, rewrite, or add to parts of them or all of them to fill in aspects that you missed the first time around.

• Use them like a script; make any changes you think appropriate on the printed page and re-record them for others to listen to.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Editing Your Life

Once you’ve got information down on paper or in digital form, you may decide to take on yourself the happy task of editing it. This may sound daunting if you’ve never done such a thing before, but can actually be a lot of fun, as it gives you a chance to shape your memories in exactly the way you want them. Basically it means you take out what you don’t want there, add things you forgot, correct things you got wrong, and in general change things so they sound better to you.

Annie Dillard, whose entire career is more or less based on the arts of personal essay and memoir, says “The writer of any first-person work must decide two obvious questions: what to put in and what to leave out.” Dillard, who produced An American Childhood, a marvelous memoir of her days growing up in Pittsburgh, is quite stringent about what doesn’t belong in her kind of memoir:

...[One] thing I left out, as far as I could, was myself. The personal pronoun can be the subject of the verb: “I see this, I did that.” But not the object of the verb: “I analyze me, I discuss me, I describe me, I quote me.”

...I tried to leave out anything that might trouble my family. My parents are quite young. My sisters are watching this book carefully. Everybody I’m writing about is alive and well and in full possession of his faculties, and possibly willing to sue. Things were simpler when I was writing about muskrats.

...I don’t believe in a writer’s kicking around people who don’t have access to a printing press. They can’t defend themselves.”

Editing your memoirs gives you another chance to decide who your audience is and shape your stories to it. If you feel a bit shaky on grammar, spelling, syntax, etc., another option is to turn your writing over to a qualified family member, or even a professional editor, for editing. An outside editor can (if necessary) correct misspellings and undangle participles, and even shape and streamline your account to make it more readable.

If you’re really lucky, you’ll find an editor (professional or nonprofessional) who’s willing to work side by side with you to get things the way you want them. If using the services of an editor, by the way, you should make it clear that you have the last word on what stays in and how it reads. It’s your story, after all.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

WRITING WITH OTHERS

Some aspiring memoir writers are solitary souls who can happily spend days on end scribbling alone in their sanctums. Others, however, are gregarious people who tend to get bogged down in solitary tasks like committing memories to paper or recordings. For these folks, there are, happily, several alternatives to going it alone.

Group Interviews/Discussions

We’ve already covered the roles of individual interviewers as catalysts in drawing out past memories, as well as ways of involving other people in your project in the role of transcribers and editors. An extension of the one-to-one recorded interview is the group interview, in which you get together with a selection of long-time friends, co-workers, family members, etc., as sources of information and inspiration.

In essence, you interview them on recorder about your shared memories—a surefire way of triggering some of your own, not to mention filling in background material. A variation on this is to have members of a memoir-writing group or class focus on interviewing one class member per session.

Participants in such a process will usually get so involved in reminiscing and story-telling that they’ll eventually forget about the presence of the recorder. If you yourself want to get deeply involved, you may want to get an outside person to take charge of the mechanics of recording this session.

One sure way to keep a memoir lively is to introduce actual dialogue into it—conversation can often give the flavor of a time and place the way description can’t begin to. If you don’t have access to a particular piece of dialogue on tape or remember the exact words of a conversational exchange; just put it down or speak it out the way you remember it.

(If any of the original speakers of a remembered dialogue are available, it may be a good idea to check with them as to how they remember it, otherwise you may hear about it later.)

Dialogue will, of course, emerge spontaneously during a taped session, but even if nary a word of your group gabfest appears verbatim in your finished memoir, such a gathering can serve to remind you of forgotten incidents or provide you with a number of different perspectives on your life and times. It can also become a great source of introduced material to enliven your account and give it a different “voice,” while still maintaining your perspective, e.g.: (“My cousin Denny remembers how we used to play spin-the-bottle under the back porch; ‘You used to get so darn mad,’ he told me, ‘because you were the littlest and nobody ever wanted to kiss you.’”)

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Writing with a Friend

Another pleasant and interesting way of working on your memoirs is to find another person who is interested in doing the same thing and get together with her or him on a regular basis (once a week is good) for the sole purpose of writing.

Unlike with the one-on-one interview process, it’s usually best that the other person not be a relative or long-time friend. The reason for this is that people who share your life may have very similar (or quite different) versions of the same events, and as a result you may wind up (1) arguing about whose version is “right,” or (2) writing in competition with each other.

It’s generally much more productive (and fascinating) to find a writing partner whose life has been quite different from yours, and who doesn’t know that much about you and vice versa, and have the fun of unfolding your lives to each other on paper.

A good way to work with a partner is to set a specific amount of time for writing in each session, a certain amount of time for on-the-spot revision, and then a reading and discussion of what each of you has written.

You may also want to designate a time at the beginning, before you each start on a new section of writing, to re-read the previous session’s work, with any revisions the writer may have made in the time between. This allows you to see more of and learn from someone else’s writing process, and also warms you up for the subsequent writing period.

You may also mutually decide to do your writing as “homework,” and limit your session together to reading, comments, rewriting and discussion. It may take a while to find your best way of working with another memoirist, but the mutual stimulation, feedback and support are well worth it.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Group Writing

Yet another approach to memoir work is to gather a group of aspiring memoirists who meet regularly (refreshments optional) to listen to, encourage, and, if appropriate, to offer constructive criticism to one another.

The key word here is constructive, and a spirit of honest helpfulness should be an understood part of the process, otherwise criticism of each other’s work is likely to descend to an unhappy level (“You split an infinitive.” “Well, I’m not particularly interested in hearing any more of your stupid stories about the Great Depression.” And so forth.)

There are also classes and workshops available in many areas, (at YMCA/YWCAs or community colleges, for example), where a teacher will happily shepherd you through the memoir-writing process. Some of these classes may even produce small books of memoir excerpts as a class project. (Maudie Sell's book, mentioned above, is the product of such a class, as was A Guest of the State, by John Van Altena, who was imprisoned in East Germany in the 1960s for attempting to smuggle out a political fugitive and got his story down as part of a college writing class.)

Both of these group situations are, at the very least, vehicles for expanding your horizons and getting to know about other people and their lives.

INCORPORATING OTHER MATERIALS

One way of achieving a change of pace and adding interest to autobiographical material is to incorporate “outside” materials, such as photographs, newspaper clippings, journal entries, letters (yours and others’), drawings, etc. All of these can be used to vary the text and add visual interest, not to mention as springboards for flights of memory.

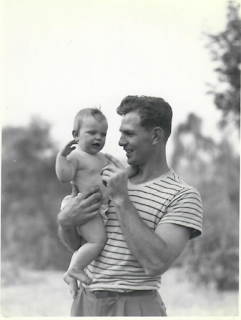

For instance, my father, when he saw the photo below for the first time in years when he was about 85, wrote the following on the back of it:“[My mother] Clara Maude Elkins Hill about 1926. We were living at the 'Ward' house in Booneville, Ark., one of my favorite places. It had a very deep well with ice-cold water."

“Mother called it “the barny house” because it was big and drafty. [My brother] Horace and I had separate rooms upstairs—there were few two-story homes in town. Mother bought a new-fangled washing machine with two tubs, an advanced concept. I think she paid $165 for it, an outlandish sum. Dad was fit to be tied."

There you have an enchanting tiny peek at one Southern family’s small-town life in the 1920s. You may find that almost any photo from an earlier stage of your life will induce a similar spill of remembered detail, not to mention providing more specific images of facial features, hairdos, clothing, buildings, animals, etc. If yours is a family with an extensive snapshot collection, you may even want to construct a photo-essay memoir, with extended captions for each picture you select.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Visuals and Sidebars

Something else that gives a memoir life is the presence of verbal “visuals,” i.e., descriptions of how the people you mention looked and dressed (not forgetting interesting facial tics/expressions and other amusing visual habits).

This also applies to describing pets and other animals, buildings, rooms, scenery, tools and objects (especially those no longer in use), jobs which people did when you were a child—anything which aids in bringing the image of these people or things to life and helps to form a visual image in the minds of your readers.

A note of caution, however, when describing inanimate objects: it’s best to think of these as backdrops or props for the activity of the people in your memoir. In other words, it may adds color to your narrative to describe briefly, interestingly and accurately such visuals as what someone was wearing (“...a daring white cotton strapless sundress with red polka-dots”); or what a room looked like (“...full of heavy mildewed Victorian furniture with faded maroon upholstery”); or an unusual job (“...his task was to stand by the conveyor belt and carefully pick out all the malformed rutabagas”).

As you do this, however, you should probably refrain from going into each tiny detail. (As soon as you get the feeling that you’re composing a list, it’s probably too much.) The time you can go into detail is when describing something which most of your readers have probably never seen, e.g. a typhoid bacillus, a Texas horned toad or a buttonhook.

If a process you’re describing, by virtue of its unusual or interesting nature, seems worthy of a real historical-grade description, you can call upon a handy advice called a sidebar. This is a little mini-essay which stands on its own and is much more descriptive than narrative. It can even have its own separate title, such as “How to Hypnotize a Chicken,” or “How We Built a Root Cellar in 1916.”

When printed as part of a book, a sidebar is usually set apart by an enclosing solid line, a change in typeface or other design elements This is to show that is an interesting addition to, but not necessarily part of, the main text. You may just want to use a different typeface for your sidebars and/or introduce them into the text in the same way you would a recipe, letting them stand on their own.

As you’re probably beginning to realize, anything you can see, smell, hear, taste or touch may be the magic trigger for a flood of memories. So can experiences like a trip to your hometown or the place where you spent your honeymoon, or speaking with a friend or relative you haven’t seen in years.

Writing your memoirs is, in short, a wonderful excuse to expand your horizons, relive your memories, connect with friends and family, exercise your brain and trot out your creativity. All that and you get to immortalize yourself for posterity as well. How can you resist?

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

WRITING MY OWN MEMOIRS, ONE THURSDAY AT A TIME

Several years ago, in response to requests by friends, I began writing my own memoirs by posting weekly "Throwback Thursday" essays, ranging from a few sentences to a dozen or so paragraphs, on Facebook. This provided me with instant feedback, not to mention the stimulus to write concisely and entertainingly. I've published these, 20 at a time, in blog form, and am now up to over 260 essays. Links to all can be found below.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

SAMPLE QUESTIONS FOR PONDERING AND INTERVIEWS

These questions are only a sample of many possible self-inquiries, and are meant to evoke memories and get you started talking. If the answer to one question reminds you of a related (or even unrelated) story, just go on to that one. You can use this list when you run out of steam, to jog your memory or get you started in another direction. You can use the list on your own, or have someone ask you the questions and make up others based on the things you remember.

Early Years

Where were you born? (area, town, city, state, country)

What are your earliest memories of your parents?

What did your childhood room look like?

Do you remember any special toys? What games did you play?

What was the neighborhood around your house like? Was it urban? Suburban? Rural? Where did you play?

Who were your playmates? Which ones did you like? Did you have a best friend? Were you bullied?

Did you have brothers and sisters? What do you remember about them from when you were young?

What did your parents do for a living?

Who took care of you? Did you stay at home, go to kindergarten or daycare, have a nanny or babysitter?

Who were your favorite adults? Favorite relatives?

Who of the people around you did you love? Who did you dislike? Who frightened you?

If you went to a church, synagogue, mosque or temple, sabbath or Sunday school, what are your early memories of them?

What was your favorite way of passing time as a child? What activities were you most drawn to?

What do you remember about holidays? Did you enjoy them or dread them? What were the biggest special occasions in your first five years?

Did you have childhood illnesses? How were you treated at those times?

Did you have an imaginary playmate?

School Days

What do you remember about your first day at school? Who were some of your outstanding teachers?

Who was/were your best friend(s) at school?

What were your favorite classes and school activities? Did you like school or hate it? Did you have a difficult or easy time learning?

Who was your favorite teacher? Did (s)he have an effect on your later life?

Was there anything unusual about your school/place of worship/town/city?

Did your family move around or stay in the same place?

Was it easy or difficult for you to make friends?

What was your favorite music?

What kind of dancing did you and your friends do?

What kinds of chores did you have to do? Did you have an allowance?

What were your feelings for members of the opposite or same sex? Did you have any crushes?

Who did you go to when you were in trouble? Who did you usually get into trouble with?

What was your relationship with your parents? How did it change in these years?

What was your proudest moment in school? your worst moment?

If you went to college, what did you study there? What were your favorite classes? What was your social life like?

Grown-Up Days

What was your first job? Did you like it or hate it? How did you spend your salary?

If married, how did you meet your spouse? What did he/she look like at the time? Where and when did you get married? What was the wedding like? Where did you spend your honeymoon?

If you served in the military, where were you stationed? Who were your friends? What was your rank? Your best memory? Your worst?

If you’ve traveled, where have you gone? With whom? By what means of transportation? What was your greatest adventure/inconvenience/moment?

What were/are your hobbies, your passions, your favorite recreations?

By now you should be getting the idea of how to ask yourself questions. General “firsts” in your life—first words, first time of doing something—are always good for some juicy memories, as are discoveries you made as you grew older. Honors and achievements are also wonderful subjects, but people would generally prefer an account of the circumstances and human interest surrounding the honor to an extended brag session or list of accomplishments. Anything you’d be curious about if it concerned someone else also applies to you.

Now’s the time to start finding your own questions. Good luck!

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

ALL OF MY BLOGS TO DATE

MEMOIRS (This is not as daunting as it looks. Each section contains 20 short essays, ranging in length from a few paragraphs to a few pages. Great bathroom reading.

They’re not in sequential order, so one can start anywhere.)

NOTE: If you prefer to read these on paper, you can highlight/copy/paste into a Word doc and print them out, (preferably two-sided or on the unused side of standard-sized paper).

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part One

https://amiehillthrowbackthursdays.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Two

https://ahilltbt2.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Three

https://amiehilltbt3.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Four

https://tbt4amie-hill.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Five

https://ami-ehiltbt-5.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Six

https://am-iehilltbt6.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Seven

https://a-miehilltbt7.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Eight

https://a-miehilltbt8.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Nine

https://amiehilltbt9.blogspot.com/

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Ten

https://amiehill10tbt.blogspot.com

THROWBACK THURSDAYS & OTHER ADVENTURES: Part Eleven

https://11tbtamiehill.blogspot.com/2021/02/w-elcome-to-my-past.html

*********************************

ILLUSTRATED ADVENTURES IN VERSE

FLYING TIME; OR, THE WINGS OF KAYLIN SUE (2020)

https://amiehillflyingtime.blogspot.com/

(38 lines, 17 illustrations)

TRE & THE ELECTRO-OMNIVOROUS GOO (2018)

http://the-electroomnivorousgoo.blogspot.com/2018/05/an-adventure-in-verse.html

(160 lines, 26 illustrations)

DRACO& CAMERON (2017)

http://dracoandcameron.blogspot.com/ (36 lines, 18 illustrations)

CHRISTINA SUSANNA (1984/2017)

https://christinasusanna.blogspot.com/ (168 lines, 18 illustrations)

OBSCURELY ALPHABETICAL & D IS FOR DYLAN (2017) (1985)

https://obscurelyalphabetical.blogspot.com/ (41 lines, 8 illustrations)

**************************************

ARTWORK

AMIE HILL: CALLIGRAPHY & DRAWINGS

https://amiehillcalligraphy.blogspot.com/

AMIE HILL: COLLAGES 1

https://amiehillcollages1.blogspot.com/

***********************************

LIBERA HISTORICAL TIMELINE (2007-PRESENT)

For Part One (introduction to Libera and to the Timeline, extensive overview & 1981-2007), please go to: http://liberatimeline.blogspot.com/